Major policy shifts are reshaping Household Credit Access in 2026, influencing loans, credit cards, mortgages, and borrowing power for U.S. households.

Table of Contents

How Major Policy Changes Could Alter Household Credit Access in 2026

Household borrowing in the United States is entering a new phase. After years of easy credit, rising inflation, aggressive interest-rate hikes, and regulatory scrutiny have changed how lenders view risk. As policymakers respond to economic uncertainty, Household Credit Access in 2026 is no longer guaranteed to look like it did in the previous decade.

For millions of Americans, credit is not just about consumption—it determines access to housing, education, transportation, and emergency liquidity. Policy decisions made today will quietly shape who can borrow, how much it costs, and who gets left out.

This blog explores how upcoming policy changes could redefine household credit conditions and what consumers should expect in the year ahead.

Why Household Credit Is at a Turning Point

The credit environment of the 2010s was defined by low rates and abundant liquidity. That era has ended.

Several forces are converging:

- Higher interest rates to control inflation

- Rising consumer delinquencies

- Political pressure to protect borrowers

- Tighter bank capital requirements

Together, these forces are reshaping Household Credit Access in 2026, making it more selective and more expensive.

Interest Rate Policy and Borrowing Costs

Central bank policy remains the most visible influence on credit access. While rates may stabilize or decline modestly, they are unlikely to return to ultra-low levels soon.

For households, this means:

- Higher monthly payments on new loans

- Stricter affordability tests

- Reduced loan sizes for the same income

Even small rate differences significantly affect long-term borrowing, especially for mortgages and auto loans.

For policy background:

https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy.htm

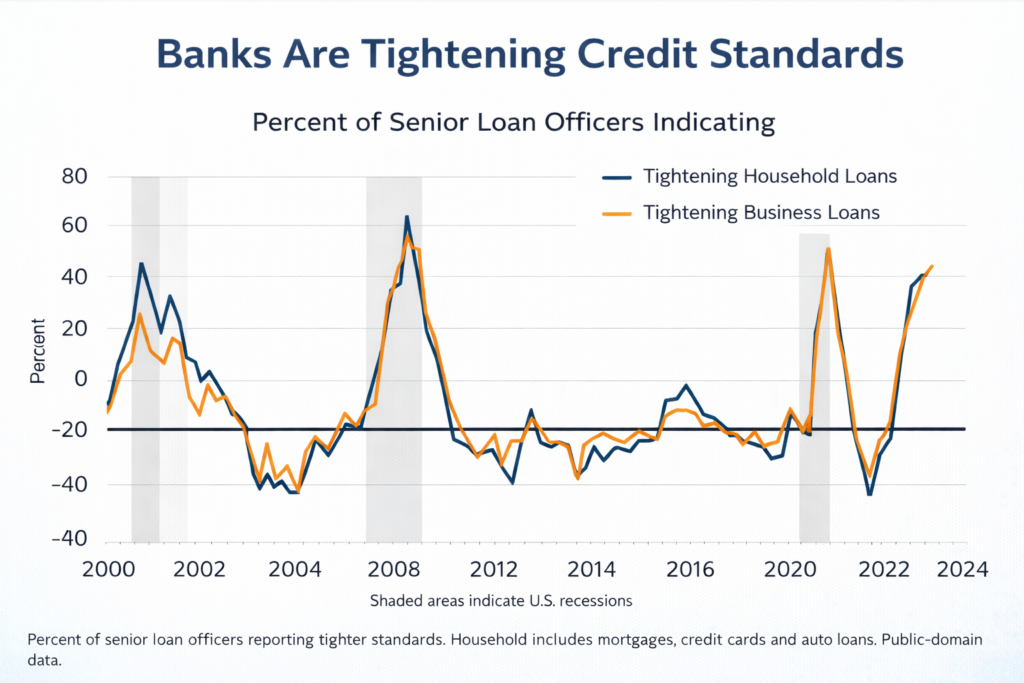

Regulatory Changes and Bank Lending Standards

Beyond rates, regulation plays a decisive role.

Potential regulatory shifts include:

- Stronger stress-testing requirements

- Higher capital buffers for consumer lending

- Closer scrutiny of subprime credit

As a result, lenders may prioritize balance-sheet safety over loan growth. This could narrow Household Credit Access in 2026, particularly for borrowers with thin credit histories or variable income.

Credit Cards and Revolving Debt Under Pressure

Credit cards are often the first channel affected by policy changes. With political focus on interest rates, fees, and consumer protection, issuers may respond by tightening approval criteria.

Possible outcomes include:

- Lower credit limits

- Fewer promotional offers

- Reduced rewards programs

While these steps protect lenders, they also reduce flexibility for households relying on revolving credit to manage cash-flow gaps.

Mortgage Policy and Housing Credit

Housing remains central to household wealth—and credit access.

Policy changes related to:

- Government-backed loans

- Housing affordability programs

- Bank exposure to real estate

could directly affect mortgage availability. Even if rates fall, supply-side housing constraints and tighter underwriting may limit borrowing capacity.

This reinforces the idea that Household Credit Access in 2026 depends as much on regulation as on interest rates.

For housing finance data:

https://www.fhfa.gov/DataTools

Student Loans and Education Credit

Education financing is another area under review. Changes in repayment rules, forgiveness programs, or federal guarantees could alter how private lenders approach student credit.

If government support expands:

- Private lenders may pull back

- Credit terms could tighten

If support contracts:

- Borrowing costs may rise

- Access could narrow for lower-income students

Either direction influences long-term household balance sheets.

Income Volatility and Risk Assessment

Lenders increasingly rely on data-driven risk models. In a labor market marked by gig work and income volatility, traditional credit scoring may disadvantage many borrowers.

Policy efforts to modernize credit evaluation could help—but without reform, Household Credit Access in 2026 may skew toward stable, higher-income earners.

This creates a risk of financial exclusion even in a growing economy.

Who Benefits and Who Loses?

Policy shifts rarely affect everyone equally.

Potential beneficiaries

- High-credit-score households

- Dual-income families

- Asset-rich borrowers

Potentially constrained groups

- Young borrowers

- Self-employed workers

- Lower-income households

As credit becomes more selective, inequality in access may widen—even without an economic downturn.

The Psychological Impact of Tighter Credit

Credit conditions shape behavior. When borrowing becomes harder:

- Consumers delay major purchases

- Spending becomes more cautious

- Savings rates may rise

These behavioral changes feed back into economic growth, making Household Credit Access in 2026 a macroeconomic issue—not just a personal one.

What Households Can Do to Prepare

While policy is beyond individual control, households can adapt by:

- Reducing high-interest debt

- Improving credit scores

- Building emergency savings

- Avoiding over-reliance on revolving credit

Preparation matters more when credit is less forgiving.

For credit-management basics:

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/consumer-tools/credit-reports-and-scores/

Looking Ahead

The coming year will test how well policy balances stability with access. Too much restriction risks slowing consumption and mobility. Too little oversight risks renewed debt stress.

What’s clear is that Household Credit Access in 2026 will reflect deliberate policy choices—not just market forces.

Conclusion: A Quieter but Deeper Shift

Credit conditions rarely change overnight. Instead, they tighten gradually—almost invisibly—until households feel the difference.

As policy priorities evolve, borrowing in 2026 will reward preparation, stability, and financial discipline. For households, understanding the direction of change may be the most valuable financial insight of all.

As Fed officials debate housing fixes, supply shortages—not interest rates—are emerging as the biggest obstacle to affordability in the U.S. housing market.